Reaching the Fulani people: Insights from Jon Banke, SIM's expert on Fulani ministries

By Vincent Wastable | West Africa

Jon, you know the Fulani well. What makes them different from the other groups they live alongside?

The fact that they are nomads is a big difference. It shapes how they see the world, which is often very different from how settled communities see things.

The acronym NOMAD is a useful tool for thinking of their distinctiveness:

● “N” for Networking: Relationships are central to the Fulani, and are especially strong within their community.

● “O” for Organised: The Fulani are organised into clans and large families. They share most everything within these family units.

● “M” for Mobility: A nomadic way of life is not random wandering. It is about a seeing mobility as a resource in and of itself, a readiness to move to access resources, like water and grazing land for their herds. As pastoralists, they feel more connected to their animals than to the land, even if they practice farming.

● “A” for Autonomy: While the Fulani do trade with others, they can manage without those connections. In many places, Fulani co-exist peacefully alongside settled peoples.

● “D” for Distinct: The Fulani see themselves as different from other groups, and others see them that way, too. Their appearance and clothing make them stand out.

The Fulani do share some things in common with the people around them. Is it possible for them to live peacefully and build good relationships?

Yes, it is. The Fulani value peace and want to live in harmony. However, in Nigeria for example, they have historically been despised and hated due to local tensions, which has led to violence. Since the 2010s, radical Muslim groups seem to have taken advantage of injustices against the Fulani, recruiting them as fighters.

An elder in West Africa is said to have declared, “If you tell me there are Fulani in heaven, I don’t want to go there.” This shows how they are often seen as outsiders and unwelcome wherever they live.

People often say that ministry among the Fulani is hard and that there aren’t many tangible results. That must be discouraging for missionaries!

We need to understand that working with the Fulani is a long-term commitment, which includes the commitment to understand who the Fulani are. We must accept that we may not see the results ourselves.

The Fulani value humility. Those who come with a preconceived plan to help or save the Fulani are not respected, though the Fulani’s politeness may imply otherwise.

In my experience, it’s not about the gospel being hard for them to accept. I think the idea that they’re unreachable is a myth. It just takes time to see results. Ultimately, we have to remember that it’s God who is doing the work.

The Bible has been translated into the Fulani language, and a number of dialects, like Borgu Fulfulde in Benin, have their own translations. How can the Bible become more treasured by the Fulani?

The complete Bible has been translated into Cameroonian Fulfulde, one of eight key dialects with translation projects. Yet, this translation is often seen as old-fashioned, like reading the King James Version. A lot of work is being done to improve literacy. When Fulani people hear the Word in their own language, it deeply moves them.

Several dialects have radio programs and broadcasts to share the Word.

Hearing the Bible spoken directly has a special power — no middleman is needed. Orality is an important tool for communicating with Fulani. It’s very important to use idioms, proverbs, and vivid imagery when sharing the message.

From your perspective, what’s the best way to reach the hearts of Fulani communities?

Making an effort and sacrificing the time to get to know them and learn their language is one of the best ways to connect. When you learn their language, you also begin to understand their culture. It’s not easy and can take years, but it’s worth it.

I wouldn’t want to be too rigid, but for me, the most effective approach is simply being with them. It’s what I call the “ministry of hanging out” — sitting with them, sharing time, and building relationships. This opens the door to talk about God, read the Bible together, and explore it with them.

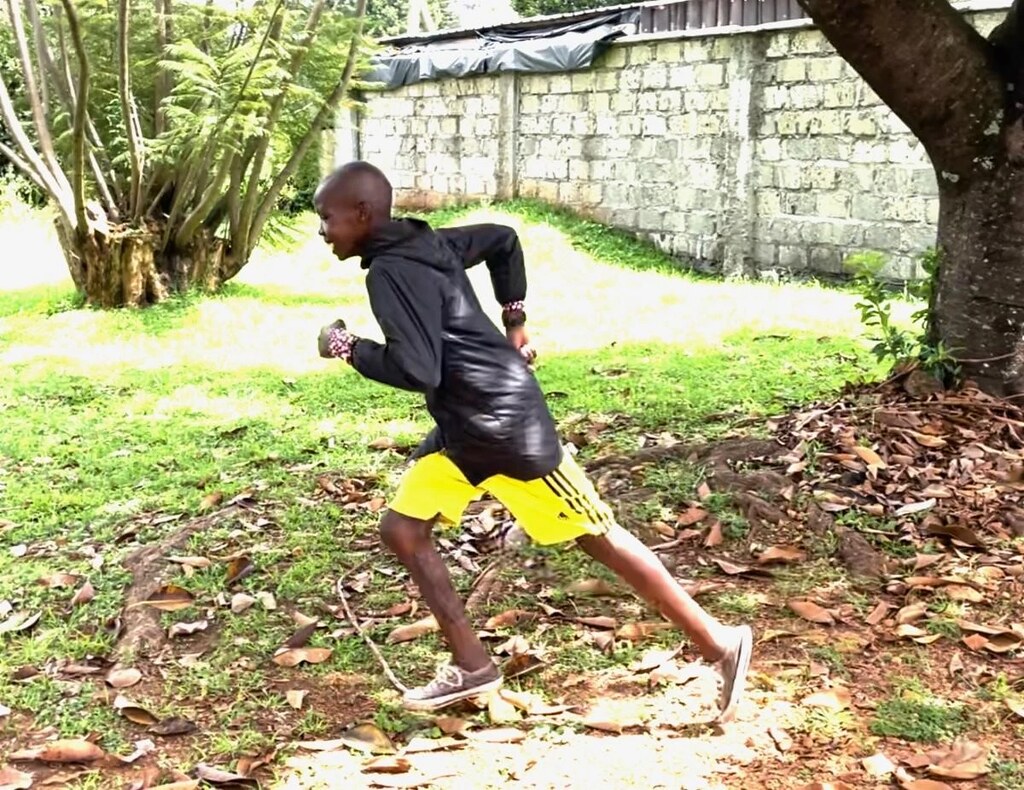

Learning their language requires time and commitment. This kind of ministry is not a sprint; it is a marathon. But if you earn trust within a Fulani community, you can truly be welcomed into a Fulani family.

You’ve been SIM’s Fulani Ministries Coordinator since 2016. How many mission workers are currently working among the Fulani?

As coordinator, my role is to act as a consultant to those working with the Fulani. I am also involved in mobilising and training new missionaries to join in this work.

Are there any positive developments?

The Fulani Church is becoming more mature and growing in both numbers and understanding of its mission. Mobilisation of the Fulani Church is a strategic and ongoing effort.

In Benin, there is an association of Fulani churches. Fulani pastors are being trained, though this is still a rare occurrence in the Sahel.

Tell us about a ministry that’s particularly close to your heart.

One ministry that stands out to me is the work of a family who ran the TIMO program in Niger from 2016 to around 2020. TIMO is an AIM programme that a two-year programme establishes teams in communities to learn the language and culture. This family had a wonderful way of living alongside the Fulani. They built simple, rustic homes, cultivated a small field, and spent time with the people.

Today, about ten people in the village are Christians, including the village chief, who was the first to come to Christ. This is a perfect example of the kind of ministry I believe is really effective.

This article has been translated from the original French version, first published in S'Immerger.

Related stories

In Carrie’s classroom, Jesus is shaping hearts and minds for his kingdom

When mission workers with young families leave their home country, a major concern is how their children will get on. While the parents are out serving, the kids need stability, education, and spiritual nurturing. That’s where teachers like Carrie come in. Originally from Kansas, Carrie now teaches at a mission school in Liberia, part of Dakar Academy in Senegal, shaping young hearts and minds for God’s kingdom.

What might God do in 2025?

As we step into 2025, there is a sense of excitement and expectancy among those serving in mission work worldwide. From remote villages to bustling cities, SIM’s Entity Directors are preparing for what lies ahead, trusting God to bring transformation and hope to unreached and underserved communities. To gain insight into their vision and prayers for the year, we spoke with leaders across the globe about their hopes, challenges, and how the global Christian community can pray and support their work.

How the local church in France adapts to secularism and a changing society

France is a country of contrasts: rich in history, arts, and culture. Yet, as French native Vincent, Head of Communications for SIM France/Belgium, explains, it is also a nation of deep spiritual need. Things are starting to change, though. There is a growing openness to faith and a pressing need for mission work.